Earlier this week, Tuesday to be specific, I posted my first review to SFFWorld in a few weeks, David Anthony Durham's The Other Lands. This is the second installment of his superb Acacia Trilogy and after finishing the third and final book recently, stands quite high in my echelon of Fantasy series.

A prologue illustrates the horrors of the Quota – the pogrom in which children are stolen and used either as slaves and/or their life force is sapped to power the boats, machines, and indeed the lives of the Lothan Aklun, one of the nations in the world. This prologue shows a glimpse of the despair and horrors of slave life and how in an instant, a brother and sister can be torn apart.

A prologue illustrates the horrors of the Quota – the pogrom in which children are stolen and used either as slaves and/or their life force is sapped to power the boats, machines, and indeed the lives of the Lothan Aklun, one of the nations in the world. This prologue shows a glimpse of the despair and horrors of slave life and how in an instant, a brother and sister can be torn apart....

In each of the first two novels in this series, the incoming leader has goals of ridding the world of the Quota, of slaves, before ascending the throne. A throne, mind you, that both times was gained through violence and the death of the previous throne’s sitter. Hanish Mein wanted to abolish the Quota, but realized how powerful a tool it was to making the world turn. Removing such a foundation proves more difficult than idealistic minds anticipate. Haunting the novel is the specter of Aliver, Corinn’s older brother who was the rightful king of Acacia. His proclamation to rid the Known World of slavery and the mist (an addictive drug used by the ruling class to keep the great unwashed populace in check) is seen by his now ruling sister as a childish dream. While the mist’s hold over the populace was broken thanks to the sorcerous events of the first novel, the Quota is still an unchangeable thing. Corinn seems to embrace the Quota and goes to great lengths to create a new tool to control the populace in the same fashion the mist was used in the past. Rather than an addictive mist, she charges her alchemists to create a wine – the Vintage – which will bring all the people who consume it fully under her sway.

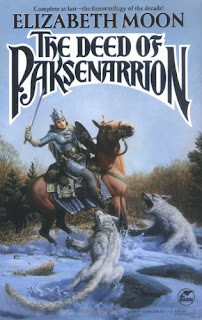

Over at SF Signal, my latest completest column is up and features the seminal Military Fantasy trilogy by Elizabeth Moon - The Deed of Paksenarrion.

One of the strongest elements of this trilogy was how that Moon chose to tell the story of Paks, not as the Hidden Heir Chosen to Rule, but rather she who finds the Hidden Heir Chosen to Rule. I liked nearly everything about the three books contained in the big grey/blue book published by Baen. What’s more impressive is that these three books are the first three published by Elizabeth Moon. I think she developed the character of Paks very well throughout the novels and the world came across as quite real, especially because of the solid and believable groundwork she laid down in the first novel Sheepfarmer’s Daughter. If you want readers to believe in the fantastic elements (elves, magic, etc.) the real elements must be authentic and true, it seems Elizabeth Moon takes that statement to heart. I’ve also seen the criticism leveled ad Paks that she’s too perfect, but a lot of her gains and successes are through hard-earned work and some suffering, she gives up part of herself in service to her goals and what she hopes to achieve, especially by trilogy’s end so it isn’t as if she just picks up a magical sword and becomes the greatest sword-wielder the world has ever seen.

One of the strongest elements of this trilogy was how that Moon chose to tell the story of Paks, not as the Hidden Heir Chosen to Rule, but rather she who finds the Hidden Heir Chosen to Rule. I liked nearly everything about the three books contained in the big grey/blue book published by Baen. What’s more impressive is that these three books are the first three published by Elizabeth Moon. I think she developed the character of Paks very well throughout the novels and the world came across as quite real, especially because of the solid and believable groundwork she laid down in the first novel Sheepfarmer’s Daughter. If you want readers to believe in the fantastic elements (elves, magic, etc.) the real elements must be authentic and true, it seems Elizabeth Moon takes that statement to heart. I’ve also seen the criticism leveled ad Paks that she’s too perfect, but a lot of her gains and successes are through hard-earned work and some suffering, she gives up part of herself in service to her goals and what she hopes to achieve, especially by trilogy’s end so it isn’t as if she just picks up a magical sword and becomes the greatest sword-wielder the world has ever seen.

Also at SFFWorld, Mark reviewed the latest massive tome edited by Ann and Jeff Vandermeer, The Time Traveler's Almanac.

It is difficult to summarize such a tome, and it would perhaps be wrong of me to try. However, like the previous Vandermeer collection, I found old personal favourites (Ray Bradbury, HG Wells, Asimov, Kuttner and Moore, Connie Willis) as well as ones totally new to me (Vandana Singh, Dean Francis Alfar, Rosaleen Love, Karen Haber, Rjurik Davidson). I found stories from authors I liked, but hadn’t read (George RR Martin, Kristine Kathryn Rusch, Adrian Tchaikovsky, Kim Newman, Eric Frank Russell) and stories I know others will like but left me cold (Ursula K leGuin, Adam Roberts). There are some old ones (Edward Page Mitchell’s The Clock that went Backward, 1881, regarded here as one of the earliest time-travel tales, Max Beerbohn’s Enoch Soames, 1916, EF Benson’s In the Tube 1923), and some relatively new ones (John Chu’s Thirty Seconds from Now, 2011, Adrian Tchaikovsky’s The Mouse Ran Down, 2012). There were some that I forgot nearly as soon as I had finished reading them, even some I disliked. But that is the nature of such an eclectic assemblage: if you don’t like one, there’ll be another along in a minute that you probably will.

No comments:

Post a Comment